I’ve had a number of conversations over the past several months that start with a riff on the same central question:

How should we reform Section 230?

My response is always the same:

What problem or problems are you trying to solve?

Invariably, the response will be something like:

There’s bipartisan consensus that we need to reform 230.

Blurg. In the minds of too many smart folks, the contours of Section 230 have transformed from levers and dials to achieve a wide array of policy objectives—broadly speaking, means for intermediating the flow of user-generated content across Internet platforms—to ends in themselves. What’s the problem? 230. What’s the solution? Reform 230.

This dynamic obscures what are, in my view, a fairly wide range of varying, sometimes overlapping, sometimes disparate, and almost always underspecified problems and solutions that are lurking beneath the tautological “we need to reform 230 because 230” framing. It’s not novel to point out that in developing policy, we ought to identify problems, diagnose root causes, and articulate and iterate on solutions, but we’ve almost completely lost that discipline in 230 conversations as they have begun to drown in the froth of partisan power politics.

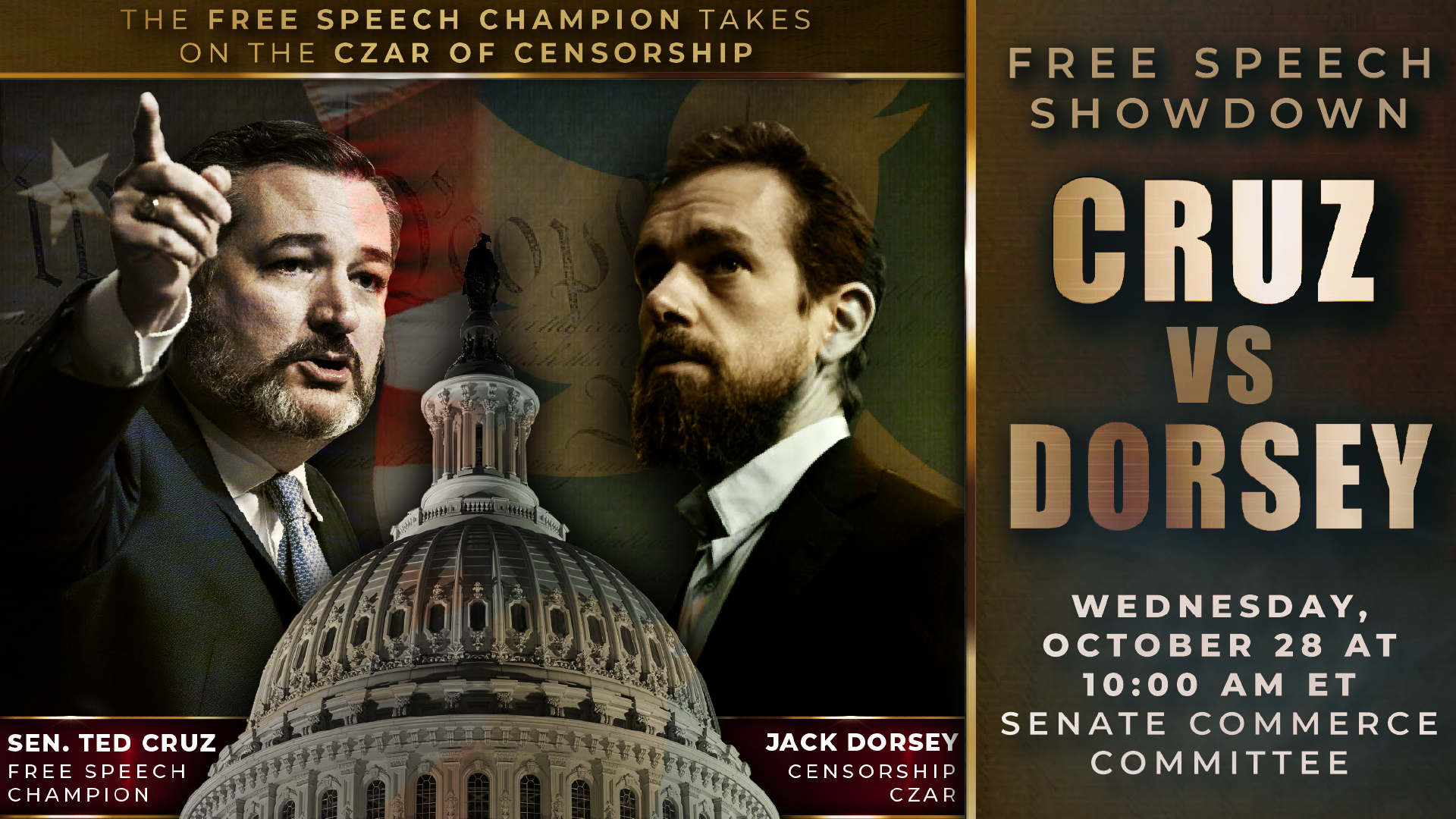

230 reform looks like a speedrun of what happened with net neutrality, which took more than a decade to transition from a weighty academic discussion to political charlatanism. We’ve quickly glitched our way past the opening levels where we’re supposed to have some serious discussion about what we’re actually trying to accomplish to the part where Senators are literally holding hearings framed as boss fights:

Nevertheless, I’ll try in this post to distill some themes that have come up in the course of a bunch of “reform 230” conversations. I hoped when I started that perhaps I could pull together an effective taxonomy of problems and solutions, but as I wrote, I became more convinced (and dismayed) that much of what’s being proposed is not much more than flinging things at the wall to see what sticks. There are some good ideas emerging from the primordial ooze, but Cam Kerry’s observation that we need serious thought- and consensus-building before we chaotically rend the Internet asunder is right on the money.

What is 230 Supposed to Do?

Before we get started, it bears acknowledging the Sisyphean problem on which Jeff Kosseff spends his life: there is so much active misinformation circulating about how 230 works (or, to borrow Mary Anne Franks’ excellent phrase, “free speech pseudolaw“) that we spend a lot of our conversations about it just trying to get people on the same page. (Jeff’s Twitter feed for the past year or so is an excellent resource for understanding that dynamic.)

I don’t want to rehash all of that here as the basics of 230 are outlined in gory detail in many other places, but I do want to highlight what I think are the two salient policy features of Section 230 that folks wading into this debate need to understand:

- As a substantive matter, Section 230 clarifies that under most circumstances, platforms can do more or less whatever they want when it comes to decisions about filtering, carrying, presenting, ordering, or taking other actions around user content, with some exceptions for things like copyright infringement and federal crimes.

- As a procedural matter, Section 230 provides platforms with the ability to easily and cheaply dispense with legal challenges to those decisions. (Jess Miers has taken to describing Section 230 as “civil procedure.”)

I’ll try and stick with this substantive-procedural frame as I go.

Repealing 230 is Not a Solution to Any Actual Problem

An instructive place to start is with calls to simply repeal Section 230 in its entirety, like the one that Mitch McConnell kinda-sorta-semi-seriously floated back in December. It’s pretty obvious that the proponents of this approach aren’t trying to solve any specific or articulable problem, unless you want to count former President Trump’s long-running (and since-escalated!) beef with Twitter. There’s a good argument that this beef itself is inherently unconstitutional, and at the very least it’s questionable that the hurt feelings of a person who has perhaps more reach for his ideas than anyone else in the whole world over a quite modest check on his ability to spread harmful disinformation do not present a problem that should warrant Congress’s attention.

(It’s also fair to point out that in January 2020, which was about 47 years ago, President Biden also made an isolated remark about repealing 230 in describing why he is not a “big fan” of Mark Zuckerberg. But President Biden has largely avoided the issue since and hasn’t signaled that he plans to invest any political capital in particular reform plans.)

Regardless (deep breath), let’s consider for a moment the implications of full-scale repeal for Section 230’s substantive and procedural features. Spoiler alert: it’s a terrible idea! But walking through why helpfully lays some foundation for the implications of lots of other reform possibilities. Setting aside the impacts of repealing the whole section on things like telecom policy, where Section 230’s findings and policy statements have played a fairly important role for the past couple of decades, let’s look at what repeal might do to Section 230’s substantive and procedural features.

On substance, it’s quite hard to predict what would be likely to happen. The scope of laws that would hold platforms liable for behavior around user-generated content but for Section 230 isn’t super clear, in part because we have had Section 230 for nearly the entire life of the commercial Internet. Section 230 gives a powerful procedural tool to dispose of claims that (a) would be likely to succeed absent 230, (b) are entirely meritless regardless of 230, and (c) everything in between. We also have loads of novel First Amendment questions about the application of a wide range of laws to platform behavior around user-generated content.

Section 230 has been remarkably effective in foreclosing the resolution of questions about the applicability of existing law to user-generated content and First Amendment barriers to those applications alike. Because we’ve had more than two decades of evolution in Internet platforms with very little legal development, it’s anyone’s guess to what a post-230 world, where every area of law from contract to tort to anti-discrimination to you-name it is fair game for conceiving causes of action against platforms, might look like.

Before we go, it’s also important to think about about the impact of full-scale repeal on procedure. Whatever a post-230 substantive world would look like, there’s good reason to suspect that the array of goofball, non-meritorious lawsuits against platforms against which 230 provides an important shield would find even greater purchase following a repeal. This is because platforms would be forced to litigate further into these cases, losing the ability to short-circuit bad arguments without having to grapple with their merits (or lack thereof).

(BT-dub, we have pretty good reason to suspect that 230 heads off a lot of genuinely meritless litigation. A survey of Section 230 cases by the Internet Association—which, to be fair, is a trade association that counts many large platforms among its members, so take it with a grain of salt—identified a fairly wide range of 230 cases where courts pointed to problems with the underlying cause of action in addition to contending with 230’s applicability. )

Stepping back, these substantive and procedural impacts can best be summarized as chaos—an open season of good, bad, and ugly lawsuits alike on platforms large and small. It should be self-evident that plunging a large sector of the economy and digital speech into unpredictable chaos without even bothering to develop a coherent problem diagnosis is a Bad Idea™.

More Specific But Still Bad Problems and Solutions

Of course, not all the reform efforts around 230 are as incoherent as the case for full-scale repeal. Unfortunately, there are a wide range of nominally more subtle ideas that don’t seem any more thoughtfully calibrated than repeal. (Caveat—there are so many 230 reform bills and trial balloons of ideas for bills floating around that I can’t even keep track of them all, so please don’t take what follows as an exhaustive list—just highlights.)

The Carveout. One of the ideas many people immediately turn to when they think they’ve identified some problematic thing that a platform does or doesn’t do is to propose exempting it from Section 230—in other words, to narrow the scope of 230’s substantive coverage. What’s wrong with that?

First off, you can’t make a category of platform behavior illegal simply by excluding it from Section 230, or require a platform to engage in some category of behavior simply by making doing so a condition of Section 230. Remember: Section 230 simply clarifies that platforms can more or less do what they want. The absence of Section 230 protection for an act or omission doesn’t alone make that act or omission illegal. There must be some additional law on the books that makes that act or omission illegal.

Another way to understand this is to look at Section 230’s existing exemptions. Almost all of the things that Section 230 exempts—federal criminal law, intellectual property law, communications privacy law, and sex trafficking law—are existing bodies of law that impose specific responsibilities on platforms. For example, Section 512 of Title 17 imposes an elaborate set of notice-and-takedown requirements on platforms for user-generated content that allegedly infringes copyright.

Here’s the rub: beyond Section 230’s existing exemptions, many of the platform behaviors that people want to address simply aren’t governed by an existing law—that is, they aren’t prohibited regardless of 230! Exempting those behaviors from Section 230 might expose the platforms to meritless lawsuits by denying them Section 230’s procedural protections, but loosing abusive litigation on platforms for doing things that aren’t illegal is an indiscriminate and underinclusive way to address whatever the perceived underlying problem is.

This is in no small part because denying 230 protections is unlikely to affect the behavior of larger or dominant platforms that have the resources to fend off abusive litigation. Most of the angst underlying these proposals seems primarily aimed at “Big Tech,” so even if the goal is just to weaponize bad litigation against the largest platforms (note that this is especially weird when it comes from folks who used to put stuff like “tort reform” in their official party platform), it’s not likely to succeed. Indeed, there’s strong reason to suspect it will simply harm the biggest platforms’ nominal competitors, who already face an enormous uphill climb against dominance and network effects.

The First Amendment. So if weaponizing indiscriminate litigation isn’t a good way to target behavior, why don’t people just pass a specific law directly regulating the particular behavior they’re concerned about? Setting aside the difficulty in getting new Internet legislation passed, regulating many of the behaviors that 230 reformers are concerned about raises First Amendment problems.

For example, many calls on the right are aimed at enacting some kind of a “political neutrality” requirement or neo-“fairness doctrine,” which (as I can only charitably guess, given the Underpants Gnoming happening in some of these proposals) would bar platforms from taking down all or most speech on the basis of its content or prevent platforms from filtering on the basis of “politics,” would almost certainly be struck down as by the courts as content- or viewpoint-based restrictions on the editorial discretion of platforms. The right isn’t alone here; calls on the left to regulate “lawful but awful“ content like hate speech or disinformation similarly would run headlong into the First Amendment.

(On the flip side, this dynamic has led “Your problem isn’t with 230, it’s with the First Amendment!” to become a clarion call for many of Section 230’s defenders. Folks should be careful with these arguments, as they often times come off as more effective critiques of the First Amendment than they do defenses of Section 230. The fact that disinformation and a flurry outright lies from political figures all the way up to the White House have led us to be mired in an out-of-control pandemic, a literal coup attempt, and conspiracy-theory fueled discord that some days looks an awful lot like a twenty-first century information civil war doesn’t cast the First Amendment in a particularly glowing light. Nevertheless, amending the Constitution is a real hassle, and folks who want to fix problems that are firmly rooted in the First Amendment are stuck with it, for better and often for worse.)

Taking Away Big Tech’s Special Benefits. Finally, some reformers, encountering the First Amendment, seem to pivot back to the carveout and say, “Aha! We’re only taking away a special government privilege, not regulating speech directly, so that can’t possibly violate the First Amendment.” Blurg, blurg, blurgity blurg. Setting aside that a “special privilege” to not get dragged underwater with a bunch of meritless lawsuits probably shouldn’t be a special privilege, the whole “Avoid the First Amendment With This One Weird Trick” maneuver isn’t so simple. Acknowledging that the underlying doctrine is what Rebecca Tushnet has characterized as an “enormous hairball,” laundering unconstitutional content-based or viewpoint-based efforts to limit private speech through an elaborate Rube Goldberg machine that spits out procedural 230 benefits if you push the right substantive buttons is not a panacea for avoiding First Amendment problems. To put it another way: if requiring or preventing a platform from doing something would violate the First Amendment, taking their 230 protections away if they do the thing you don’t want or don’t do the thing you do want isn’t necessarily more constitutionally copasetic.

“You Law Professors Are Always So Focused On Problems.”

At this point in the conversation, a lot of folks start getting frustrated with me and slowly transform into the Internet policy version of Oscar Rogers—”What are we going to do to FIX IT?” Of course, I’m a law professor, not a magician, and it’s challenging to FIX IT when we have no serious consensus on what ‘IT’ is. Seriously—we need to have real conversations on what we’re trying to accomplish here instead of endless hearings with tech company CEOs that primarily feature performative outrage in lieu of substance. Nevertheless, there are some potentially workable ideas for solving more well-articulated problems being workshopped off-Broadway while Congressional Partisan Techlash Theater continues apace.

Focus on Specific Substantive Behaviors and Responsibilities. Though the problems with some of the harmful and/or unconstitutional carveouts being proposed to 230 might lead someone to think that no Internet platform can ever be regulated ever without the world coming to an end, that’s not the case. On the substantive side of the fence, there are lots of reasonable candidates for tort and anti-discrimination laws that would impose reasonable and important responsibilities on platforms consistent with the First Amendment, and there’s no doubt that Section 230 can get in the way. For example:

- Harvard was partially successful in asserting Section 230 to defend against an lawsuit under the Americans with Disabilities Act by the National Association of the Deaf for failing to caption many of its videos, even though closed captioning mandates have been repeatedly upheld against substantive First Amendment challenges.

- Advocates like Carrie Goldberg have outlined the ways in which 230 has impeded the enforcement of tort laws under egregious circumstances involving the abusive leveraging of platforms for unconscionable acts of virtual and real-world harassment, even as courts recognize that many abusive and harassing acts can be regulated consistent with the First Amendment.

- My colleague Gus Hurwitz (from the slightly less good state to the east of Colorado) has written about the possibility of imposing traditional products liability law on online retailers like Amazon when they do stuff like, you know, sell broken products that hurt people.

This isn’t to say these are easy rows to hoe (as they probably say in that east-of-Colorado state). There are often substantive challenges in working through how pre-Internet anti-discrimination and tort laws should apply to the Internet. There are complicated technical questions that might be better solved by specialist expert regulators than lay judges, and legal questions that may require legislation to refine even before 230 comes into the picture. Properly scoping categorical carveouts get very complicated when we’re talking about state statutes and common law, as privacy preemption advocates have discovered. And I readily concede that the well has been poisoned by the extraordinarily harmful efforts to push poorly-thought out exceptions to Section 230 in the FOSTA/SESTA fight.

Nevertheless, I think folks should be more open to the possibility of carving out from Section 230 specific, well-justified and articulated legal regimes for imposing responsibility on platforms that can be readily squared with the First Amendment. There are some 230 defenders who seem overly stuck on the fact that everything that happens on the Internet is inherently bound up with content and speech. We’d get further in these conversations if everyone could at least acknowledge that the Internet gives root to real problems that cause real harm to real people, even if they are opposed to specific legal interventions on balance.

Procedural Carveouts. There‘s another array of ideas around tinkering with 230’s procedural protections. These include things like transparency—mandating that platforms provide more detailed information about how they moderate content—or the creation of notice-and-takedown regimes, like the one that we have under Section 512 for copyright infringement.

More transparency seems to me like a nominally good or at least unobjectionable idea, though I do wonder what problems it is supposed to solve. For powerful, dominant platforms, transparency obligations might make it nominally harder to lie about what they do, but it’s always fairly easy for platforms to be vague—or just to be honest that they’re doing things you don’t like! I’m skeptical that transparency alone is a path to meaningful behavioral change absent other market or democratic forces to hold powerful platforms accountable—knowing the nature of oppression is all well and good but it’s also nice to be able to do something about it. (That said, there is a lot we could do to reform laws like the CFAA and Section 1201 of the DMCA, which make it harder for smart researchers to kick the tires on how platforms actually work.)

There are also some efforts to lever transparency into an enforceable law—i.e., to require platforms to follow their own rules and punish them when they don’t. I tend to fear that letting platforms set the scope of public law can lead to underinclusive results—when platforms weaken or make vague their own rules—overinclusive ones—when platforms specify strict rules that sweep in more content than they meant to—or confusing ones, when figuring out whether platform rules cover a situation or not. Folks who are experts on content moderation have conducted endless educational efforts on how hard content moderation is to do at scale, and while I think this is often more of a damning indictment of platforms operating at scale than anything else, I’m not sure how much punishing inevitable failures is going to make them any less inevitable.

Notice-and-takedown regimes are an interesting option. On the one hand, we have two decades of cautionary tales about N&T from Section 512, and they are replete with abuse, private agreements that skirt the contours of the law, and endless debates about burden shifting. I think these issues are only likely to be exacerbated by expanding beyond copyright infringement, which is hugely complicated but way less so than the full range of legal regimes—including individual platforms’ own policies, maybe?—that are likely to be wellsprings for N&T regimes.

On the other hand, many of the worst fact patterns in 230 cases, from Zeran to Herrick, stem from platforms failing to take action on totally egregious content and leaving victims of abuse with no remedy. If you’re completely allergic to letting lawsuits go through, I think it’s incumbent on you to be open to more modest approaches to give victims some kind of recourse. (I’d be remiss not to point to Daphne Keller’s excellent Who Do You Sue?, which chronicles the converse situation that users can find themselves in when platforms unfairly take content down, sometimes as a result of jawboning by the state.)

There Are A Bunch of Other Areas of Law and Policy! Of course, all these conversations about Section 230 are happening adjacent to enormous fights about the future of competition law and policy—particularly antitrust— privacy law, and telecom law that could have tremendous impacts on how some platforms’ business models can work, and in turn how they moderate content and behave more generally. This blog post is already too long for a deep dive, but lest anyone think I’m just trying to defend platforms here, some of the big companies have fundamentally harmful surveillance-oriented architectures and engage in acquisitions that all feed into a scale of operation that exacerbates some of the harms that might superficially seem more connected to Section 230.

To cite a not-so-hypothetical example: funneling all the world’s communications through a single ubiquitous network with a single person at the helm whose perspectives on content moderation seem to be rooted in dorm-room-level philosophy about free speech, man, is a profoundly dangerous idea. That’s before we get to what is probably the most profoundly manipulative engagement model since cigarettes and such flagrantly anticompetitive behavior that even people building hotels on Park Place and Boardwalk before they pass Go and collect $200 are like, “whoa, now that’s a Monopoly™.” But I’m not sure how futzing with Section 230 is going to fix any of that.

There Are A Bunch of Other Countries! Last thing: as my elite colleagues who have been to Europe before often observe, there are [total number of countries in the world] minus one countries in the world that don’t have the First Amendment, and radically different things can and are happening there. Maybe we should learn about them! (That’s what we in the business call a Teachable Moment™.)

I’ve gone on long enough, but hopefully this post helps illustrates this dismal state of our discourse on 230 and some potential directions for making it better. I’m always happy (well, not like happy, but you know what I mean) to chat about this stuff, so just gently smash that “e-mail” button above if you want to get in touch. Good luck! (And don’t forget to cite the statute correctly!)